The Golden City

Situated on the banks of River Chenab, Multan ranks as the 7th largest city of Pakistan. Having rested on decades of historical conquests and transformations, Multan remains the heart of Southern Punjab and a prominent cultural and economic center. Multan is the oldest city in Pakistan, dating back to the 7th century. It has witnessed the conquests of Ghaznavids, Alexander the Great, the Mughals, and so on. Given the ancient nature of the city, a famous Persian poet writes:

چهار چيز است تحفه در مولتان…..گرد وگرما گدا و گورستان

(Four things are Gifts of Multan. Dust, Summer, Saints, & Graveyards)

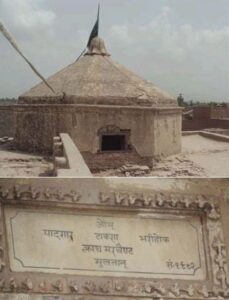

These poetic verses aptly encapsulate the essence of Multan by highlighting its arid yet windy climate and its decades-old relation with Islamic Mysticism and even Hinduism. For this, Multan is popularly known as “the city of saints.” The city not only served as a hub for Muslim saints, but before partition, Multan also used to be a spiritual destination for Hindus who resided here and even for those who traveled to the city to visit the sacred temples and shrines of their saints. If the history of Multan is studied, it is revealed that the city once radiated and thrived on inter-faith harmony. Many will be surprised to know that the Hindu festival of Holi originated from Multan. The Prahladpuri temple surviving to this day is a testimony to this fact.

Multan, the home of Sufism, has nurtured many shrines, temples, mosques, and ornate tombs. Among these, the shrines of Hazrat Baha-ud-Din Zakariya and Hazrat Shah Rukn-e-Alam are famous for their grandeur and unique architecture. Having historical roots, Multan’s culture is enriched with music, poetry, arts, and crafts. The city produces unique and traditional handicrafts such as blue pottery, Kashi tiles (blue glazed tiles), camel skin and bone lamps, Khussas (traditional shoes), and embroidered clothes. The city and region have given birth to icons of music and poetry.

Blue Pottery.

The Land Lost

Despite the historical significance and rich cultural landscape of Multan, the city’s relevance is on a decline. This can be gauged from the current condition of the walled city of Multan. The city used to have six gates but, due to neglect, has been reduced to only three. Many architects and urban planners agree that the historical decline began soon after partition when the indigenous Multanis migrated and new people settled in. This is true to a certain extent, but abandonment at the hands of our government and bad bureaucracy has added to the deteriorating nature of heritage in Multan. Nayyer Ali Dada, architect, and member of the heritage conservation board, exclaims that, “we have reached our rock bottom, and the problem is our rock bottom is quicksand. Thus, it doesn’t stop there; it keeps on going down”. With the out-migration of the natives and influx of new people, the value placed on heritage has also changed. This can be witnessed by the increasing nature of commercialization in the walled city of Multan. Entire neighborhoods and residences have been turned into warehouses and storage facilities. The relics of the past are now being used as engines of economic development.

Multan city and its Hindu temples stood as reminders of the interfaith harmony which once existed between Muslims and Hindus. After partition, these temples were reduced to the heritage of the minorities and were soon the victim of Muslims’ brewing intolerance and bigotry. The 1992 Babri Masjid demolition fueled extremist sentiments across the border, and the period following this witnessed the destruction and wreckage of many Hindu shrines and temples.

Ahmad Tahir—architect, urban planner, and resident of Multan—expressed that the lack of infrastructural investment and development in Multan has also added to the city’s decline.

According to him, provincial government and municipalities lack the power to make decisions that involve the demands and wishes of people. Ad hoc based development initiatives are being taken, which reflect the ignorance of the on ground reality of people and the city. He highlighted how authorized discourse around heritage only promotes monumentality, grand scale, and the idea of inheritance, which means that preservation efforts for historical sites are only made for commodification. This further complicates the scenario for locals as the tourist potential of historical sites is prioritized, whereby meanings and cultural values associated with the natives and locals are overlooked. Even the efforts to protect and preserve heritage are half-baked, and the National Antiquities Act of 1975 is an example. An act that has been passed in the spirit of conservation ironically only protects heritage sites in the city which are more than 75 years old.

In addition, to revitalize and reinvigorate the spirit of heritage, international actors are being involved. In Multan and its walled city heritage, “Sustainable, Social, Economic and Environmental Revitalization” of the Walled City Multan project (SSEER) was initiated between Italy and Pakistan governments. Such initiatives only act to undermine and exploit historical areas’ tourist potential, whereas efforts to benefit the residents of these places are further overlooked. It is ironic how the government aims to foster tourism in the city when it cannot support it. Dr. Muzammil, a tour operator in Multan, said “that few people are interested in visiting the city due to poor facilities, costly accommodation, and negligence by the authorities”. Multan in its current state only attracts religious tourism whereby devotees

make their way to different shrines to pay homage to their pledged saints, he added

However, religious tourism has also suffered a decline due to increased terrorist activities and sectarian violence. Thus, the relevance of the city in the present and its tourist potential paints a gloomy picture whereby its ancient and historical nature is losing traction