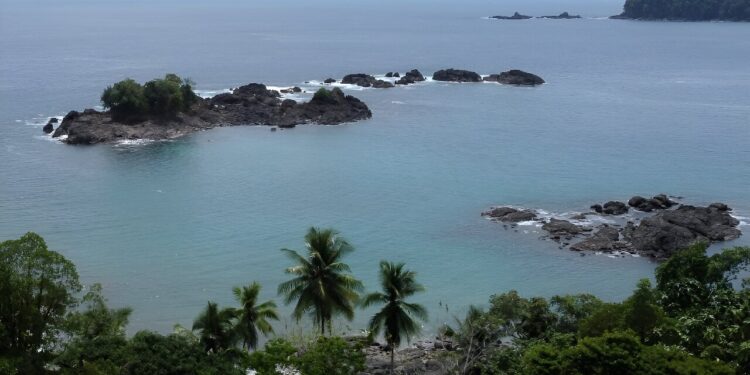

In the remote west of Colombia, where virgin rainforest and pristine beaches collide, a group of politicians and businessmen dreamed of building a massive port on the Pacific.

It took almost two decades, but a small community managed to sink the project, betting on a different development model to preserve their slice of paradise.

In June, UNESCO declared the Gulf of Tribuga a biosphere reserve, putting a definitive end to plans to build a deepwater port and some 80 kilometers (50 miles) of highway through the untouched jungle.

The remote region, with no roads linking it to the interior, boasts a bounty of plant species, while its warm Pacific waters are a breeding ground for humpback whales and turtles.

In a region where unemployment stands around 30 percent, and poverty affects some 63 percent of inhabitants, the project promised “a lot of jobs,” recalls Marcelina Morena, a 51-year-old Columbian of African descent.

“But on the other hand, it was going to bring us destruction of the mangroves, the land, everything. So we said no to the port.”

Wearing rubber boots and gloves, she clambers through thick mangrove branches in search of pianguas, a mollusk considered a delicacy in Ecuador and Mexico.

She says the Gulf of Tribuga “is going to be for the children, so that in the future they have something to live on.”