In April 2025, following the tragic Pahalgam attack, India’s Cabinet Committee on Security took a step that threatens to unravel one of the most resilient achievements of international cooperation in South Asia: the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT). By holding the 65-year-old agreement in “abeyance” and vowing to divert waters to Rajasthan, New Delhi has not only breached its legal obligations to Pakistan but has weaponized the most fundamental resource of life itself—water—putting the human rights of 240 million people at grave risk.

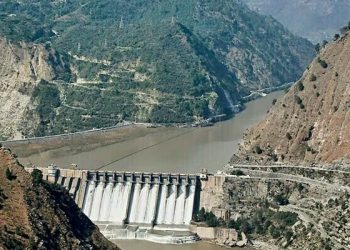

The IWT has survived wars, nuclear tests, and decades of hostility precisely because both nations recognized that water flows must transcend political enmity. The treaty allocates the western rivers—Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab—to Pakistan, irrigating 18 million hectares of farmland that constitute 80% of Pakistan’s arable land and generate nearly a quarter of its GDP. For a nation already ranked among the ten most vulnerable to climate change, with limited water storage capacity, the unimpeded flow of these rivers is not a diplomatic luxury; it is the difference between food security and famine, between livelihood and destitution.

India’s decision to suspend the treaty, justified as a response to “cross-border terrorism” and alleged “fundamental changes in circumstances,” collapses under legal scrutiny. In June 2025, and lately in February 2026 the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) delivered a clear verdict: the IWT “does not allow either Party, acting unilaterally, to hold in abeyance or suspend” its obligations. Article XII(4) explicitly states the treaty continues until terminated by mutual consent through a duly ratified new agreement. By attempting to unilaterally alter this arrangement, India violates the very foundation of treaty law—that pacta sunt servanda, agreements must be kept.

The legal justifications offered by India—population growth, energy needs, and security concerns—fail to meet the stringent criteria for treaty suspension under customary international law, reflected in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT). The doctrine of rebus sic stantibus (fundamental change of circumstances) requires changes that imperil a state’s existence or render obligations “essentially different” from those originally undertaken. Mere demographic shifts or clean energy ambitions do not meet this threshold. Similarly, the claim of “material breach” by Pakistan falters; disputes over hydropower projects were already subject to the treaty’s sophisticated dispute resolution mechanisms, which India has increasingly circumvented rather than utilized.

Even if one accepts India’s security concerns—a proposition requiring credible evidence linking the Pahalgam attack to Pakistani state actors that New Delhi has not publicly disclosed—the suspension of water flows cannot qualify as a lawful countermeasure. Under the International Law Commission’s Articles on State Responsibility, countermeasures must be proportionate, temporary, and reversible, and must not affect obligations for the protection of fundamental human rights. Deliberately disrupting water supplies to a nation of 240 million people, threatening their rights to food, water, health, and development, is neither proportionate nor reversible. It is collective punishment masquerading as statecraft.

The human rights implications are catastrophic and immediate. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has affirmed that states must refrain from actions that interfere with the right to water in other countries, emphasizing that “water should never be used as an instrument of political and economic pressure.” Yet India’s Home Minister has declared India will “never” restore the treaty, proposing instead to divert western river waters to Rajasthan—a move that would permanently sever Pakistan’s agricultural lifeline. Such actions violate not only treaty obligations but erga omnes duties to prevent significant transboundary environmental harm, recently affirmed by the International Court of Justice as foundational to international law.

Beyond the immediate humanitarian crisis lies the unresolved wound of Jammu and Kashmir, perpetuated by the persistent non-implementation of United Nations Security Council resolutions mandating a plebiscite to determine the region’s future. The IWT’s suspension cannot be divorced from this dispute that has poisoned relations between these nuclear-armed neighbours for decades, demands urgent resolution of the Kashmir dispute accordingly. As the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy recognizes, protracted unresolved conflicts create conditions conducive to terrorism. By escalating water disputes rather than addressing the root causes of regional instability, India risks transforming a manageable technical disagreement into an existential conflict, potentially triggering Pakistan’s declared characterization of water diversion as an “Act of War.”

The path forward requires immediate de-escalation and legal compliance. India must restore the IWT without conditions, participate in good faith in the PCA proceedings it has boycotted, and abandon plans to divert transboundary waters. The international community must recognize that in an era of climate crisis, water cannot become a tool of coercion. The right to water is universal, non-negotiable, and non-derogable.

Sixty-six years ago, leaders scarred by partition chose cooperation over conflict. Today, with the climate crisis deepening and regional tensions simmering, that wisdom is needed more than ever. To sacrifice the Indus Waters Treaty on the altar of political retaliation is to endanger not just Pakistan’s future, but the very possibility of peaceful coexistence in South Asia. Water must flow; so, must diplomacy.