South Asia is no longer insulated from global power politics. The rivalry between the United States and China has entered the Himalayan theater and Jammu and Kashmir now sits at the intersection of that contest. What appears on the surface as a localized territorial dispute is, in reality, a node in a widening strategic triangle involving India, China and the US.

India’s foreign policy over the past decade has been driven by a central assumption: alignment with Washington would provide strategic leverage against Beijing. This logic shaped India’s Indo-Pacific rhetoric, defence cooperation with the US and its participation in minilateral groupings aimed at balancing China. The expectation was clear, closer ties with the US would strengthen India’s hand in its border disputes and enhance its regional standing.

That assumption has not translated into outcomes.

The United States views India as a useful partner in balancing China, but not as a treaty ally. Washington’s commitments remain flexible, interest-based and subject to domestic political change. India, however, structured part of its China strategy around expectations of long-term American backing. This created a strategic gap between India’s ambitions and the actual guarantees available.

China, by contrast, has followed a linear and consistent strategy. It has not relied on symbolic diplomacy. It has relied on geography, infrastructure and positional leverage. Nowhere is this more visible than in areas connected to the broader Kashmir region.

The Shaksgam Valley illustrates this shift. Located along the China–Pakistan frontier, its status is linked to the Pakistan–China Boundary Agreement signed in Beijing on 2 March 1963. Under this agreement, Pakistan recognized Chinese control over Shaksgam, while China acknowledged Pakistan’s position elsewhere. A boundary demarcation protocol followed in 1965. The agreement remains valid between the two signatories.

India rejects this arrangement, claiming the territory as part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. Yet China’s position has not shifted. Beijing treats the area as sovereign Chinese territory and asserts its right to develop infrastructure there. This includes connectivity projects that intersect with the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, one of the flagship components of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This is not symbolic positioning. Infrastructure changes realities. Roads, logistics routes and construction projects transform cartographic claims into operational control. They create permanence. India’s responses, in contrast, remain largely diplomatic and rhetorical.

This asymmetry matters because Jammu and Kashmir is no longer insulated from major power politics. India presents Kashmir as an internal and settled issue. Yet China’s posture directly contradicts that narrative. A permanent member of the UN Security Council does not recognize India’s claim over the entire former princely state. That alone carries diplomatic weight.

China’s stance also aligns with Pakistan’s long-standing argument that Kashmir remains disputed under international frameworks. This convergence is strategically significant. When a global power’s territorial practice overlaps with a regional dispute, the issue ceases to be confined. It becomes structurally international.

The United States adds another layer of complexity. Washington does not endorse China’s position, but it also avoids direct entanglement in India’s territorial claims. The US prioritizes stability and its broader competition with Beijing. It encourages India as a balancing force but avoids commitments that would draw it into Himalayan disputes. This leaves India in a difficult position: strategically encouraged, but not strategically guaranteed.

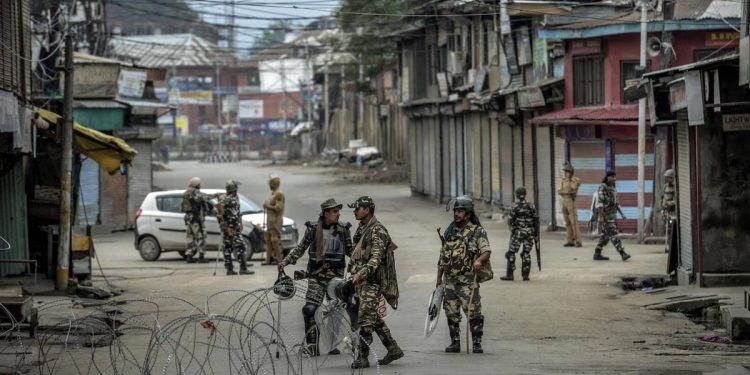

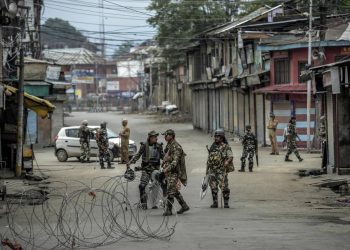

India therefore faces pressure on two fronts. China applies material pressure through border posture and infrastructure expansion. The US applies strategic expectation without hard commitments. Between these poles, India must manage an unresolved border, a sensitive internal security environment in Jammu and Kashmir and a contested international narrative.

The internal-external divide that India seeks to maintain on Kashmir is increasingly porous. Developments in Shaksgam, Ladakh and surrounding areas show that border infrastructure, military deployments and diplomatic signaling are interconnected. Kashmir is not just a domestic governance issue; it is part of a regional power equation.

China understands leverage in spatial terms. Control of heights, corridors and connectivity routes produces negotiating power. India’s diplomatic protests do not neutralize physical consolidation on the ground. Over time, material realities influence political outcomes.

The broader risk is strategic miscalculation. India operates with shrinking maneuvering space. Its US partnership cannot be assumed as a security umbrella. Its China outreach has not resolved core disputes. Yet the territorial contest continues to evolve.

Jammu and Kashmir therefore becomes more than a bilateral dispute or an internal constitutional matter. It becomes a frontier in great power competition. That transformation carries long-term consequences. Once a dispute is tied to major power rivalry, de-escalation becomes harder, compromise becomes costlier and symbolism becomes insufficient.

China has demonstrated consistency. The US has demonstrated conditional engagement. India must now confront a reality where strategic alignment has not removed territorial pressure. In this environment, ambiguity weakens positions rather than preserving flexibility.

The Himalayan region is shifting from a peripheral borderland into a strategic hinge of Asian geopolitics. The question is no longer whether Kashmir is internationalized in rhetoric. It is being internationalized in practice, through power projection, infrastructure and great power competition.

That is the real transformation underway and it is reshaping the strategic future of the region.