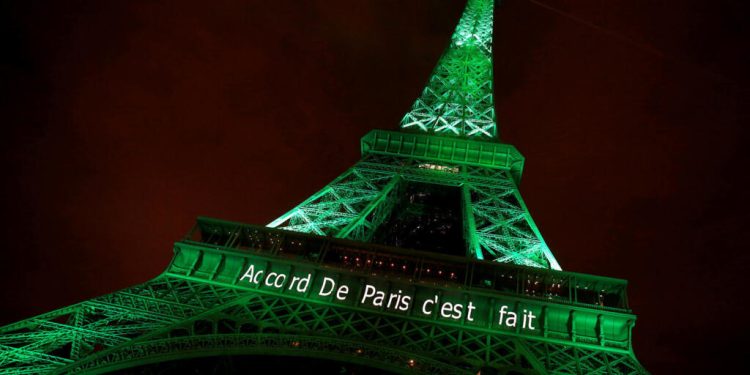

Ten years after the Paris Agreement was signed on 12 December 2015, the world is warming faster than countries are cutting emissions – even as clean energy expands and projected future warming has fallen.

Earth has warmed by about 0.46C since the deal was signed and the past decade has been the hottest on record. Scientists say governments have not moved fast enough to break dependence on coal, oil and gas, even though the accord has helped lower long-term temperature forecasts.

Johan Rockstrom, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research, warned that the gap between action and impacts has grown as temperatures continue to rise and extreme weather intensifies.

“I think it’s important that we’re honest with the world and we declare failure,” he said, adding that climate harms are arriving faster and more severely than expected.

Other voices point to progress the agreement has helped drive. Former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres said momentum has exceeded expectations.

“We’re actually in the direction that we established in Paris at a speed that none of us could have predicted,” Figueres said. The pace of worsening weather, she added, now outstrips efforts to cut emissions.

UN agencies have also warned that the world is not keeping up. UN Environment Programme head Inger Andersen said the world is “obviously falling behind”.

“We’re sort of sawing the branch on which we are sitting,” Andersen said.

Rising heat, rising losses

Each year since the Paris deal has been hotter than 2015.

Deadly heat waves have struck India, the Middle East, the Pacific Northwest and Siberia. Wildfires have burned across Hawaii, California, Europe and Australia. Severe floods have hit Pakistan, China and the American South.

Researchers say many of these disasters show signs of human-driven warming.

More than 7 trillion tonnes of ice have melted from glaciers and the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets since 2015. Sea levels have risen by 40 millimetres over the decade.

Research in medical journal The Lancet warns global economic losses tied to extreme weather reached about $304 billion last year.

Global greenhouse gas emissions reached a record 53.2 gigatons last year. Two-thirds came from China, the United States, the European Union, India, Russia, Indonesia, Brazil and Japan. Only the EU and Japan cut their annual totals.

Green power

The past decade has seen progress in other respects, notably renewable energy.

Renewables now supply 40 percent of global electricity and overtook coal in the first half of the year, with wind and solar covering all new demand.

According to UN assessments cited in expert analyses, solar is now 41 percent cheaper than fossil fuels and onshore wind is 53 percent cheaper. Clean-energy investment surpassed $2 trillion in 2024, double fossil-fuel spending.

Electric vehicle sales have climbed from about 1 percent of global car sales in 2015 to nearly a quarter.

“There’s no stopping it,” said Todd Stern, a former US special climate envoy who helped negotiate the Paris deal. “You cannot hold back the tides.”

Yet fossil fuels still supply about 80 percent of global energy, the same share as in 2015.

A narrowing window

Without the Paris deal, scientists say the world may have headed for about 4C of warming by 2100.

Existing national plans point to roughly 2.3C to 2.5C if fully delivered. Current pledges would cut emissions by about 10 percent between 2019 and 2035.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN’s climate science body, says they need to fall by 60 percent by 2035 to keep the 1.5C limit in reach.

Developed countries pledged $300 billion a year by 2035 at Cop29 in Baku last year, far below what developing nations say they need.

“The Paris Agreement itself has underperformed,” said Joanna Depledge, a climate negotiations historian at the University of Cambridge.

“Unfortunately, it is one of those half-full, half-empty situations where you can’t say it’s failed. But then nor can you say it’s dramatically succeeded.”