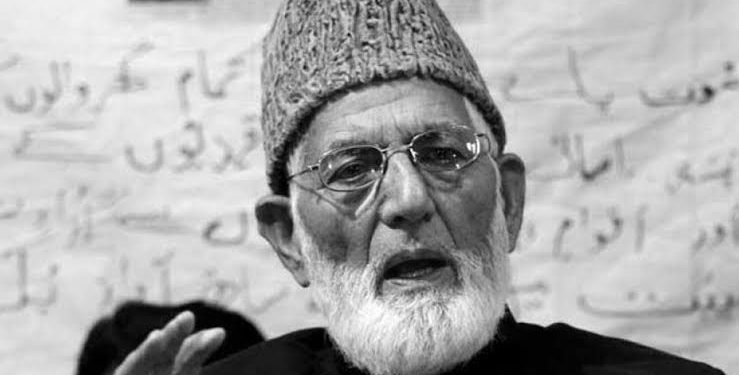

Born in the quiet Bandipora village and raised in the town of Sopore, Syed Ali Shah Geelani emerged as one of the most uncompromising and enduring figures of the Kashmiri resistance movement. His academic journey took him to Oriental College Lahore, where he pursued a passion for languages and literature, eventually becoming the author of at least 34 books. Among his notable contributions was the translation of Allama Iqbal’s Persian works into Urdu, a task that reflected not only his literary depth but also his ideological alignment with Iqbal’s vision of Muslim revival.

For over seven decades, Geelani’s life remained intertwined with the political fate of Jammu and Kashmir. As lifetime chairman of the All Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC), and previously as a leader of Jamaat-e-Islami and later Tehreek-e-Hurriyat, he carved out a political identity defined by resilience and resistance. His last 11 years were spent under house arrest, suffering from multiple health complications, yet even physical confinement could not dim the symbolic power of his voice. To his supporters, he was not merely a politician but an icon – a living embodiment of the Kashmiri aspiration for self-determination.

In my view, what sets Geelani apart from many others in Kashmir’s tumultuous political landscape is his unwavering ideological clarity. When other Hurriyat leaders began to soften their positions towards New Delhi, Geelani chose defiance over compromise. He broke away and formed Tehreek-e-Hurriyat, insisting that Kashmir must be recognised as a disputed territory, and its fate determined only through a UN-mandated plebiscite. This firmness came at a heavy price – decades in prison, isolation, and relentless surveillance – but also earned him unmatched credibility among large sections of Kashmiri society.

Unlike many leaders who oscillated between rhetoric and accommodation, Geelani was consistent, almost stubborn, in his politics. His pro-Pakistan stance was absolute, rooted in the two-nation theory. To him, Kashmir belonged with Pakistan, although he once admitted that independence was still preferable to what he called “Indian imperialism.” In the eyes of his critics, he was rigid and outdated; in the eyes of his admirers, he was principled, uncompromising, and authentic. Senior Indian journalist Yoginder Sikand described him as perhaps the only Kashmiri leader regarded by many as “honest” and “unparalleled” in symbolising resistance to Indian rule.

What makes Geelani’s story human, however, is not just his politics but also his defiance of mortality. Surviving more than a dozen assassination attempts in two decades, Geelani lived like a marked man, yet refused to retreat. He openly criticised even Pakistan when he felt it betrayed Kashmiri interests, particularly during the Kargil conflict. His rejection of General Pervez Musharraf’s four-point formula further cemented his reputation as the man who would not bend, not even before those he was ideologically aligned with.

For many young Kashmiris, Geelani was compared to Omar Mukhtar, the Libyan freedom fighter who refused to compromise with Italian colonial rule. Like Mukhtar, Geelani came to embody not just resistance, but the moral authority of saying “no” when silence or compromise would have been easier.

Syed Ali Shah Geelani’s legacy is not about victories won or territories liberated – it is about the endurance of a voice that refused to be muted. Whether one agrees with his ideology or not, his life remains a reminder that in a world of shifting allegiances and diluted convictions, there are still men who choose principle over power, defiance over diplomacy, and struggle over surrender.